The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Many Hurdles Remain

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is a major free trade agreement currently being negotiated between twelve Pacific Rim nations. The talks grew out of a smaller agreement between Singapore, New Zealand, Brunei, and Malaysia nearly a decade ago, but have since expanded to include Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico, Peru, the United States, and Vietnam. The TPP has received widespread attention due to its massive size and expansive scope. In addition to the participation of two of the globe’s three largest economies, the United States and Japan, the pact could eventually include South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and the Philippines, though these countries are not directly involved in the current negotiations. China, the elephant in the room for any Pacific trade pact, is not a party to the TPP talks and has only hinted interest, according to the Obama administration.

TPP negotiations are held in secret until a final deal is reached, a significant departure from prior FTA negotiations. Though many of the details remain unknown, the broad framework of the deal has been widely reported.

The Obama administration has actively sought the TPP as a part of its “pivot to Asia,” despite significant resistance from traditional Democratic constituent groups, especially labor unions. The administration overcame a major hurdle earlier this summer when it was granted ‘fast-track’ approval from Congress. Fast-track allows the administration to negotiate a final deal, which would then be brought to Congress for an up-or-down vote. Without fast-track status, members of Congress could have further amended the agreement after the negotiations concluded, making a deal all but impossible. U.S. Congressional approval, however, is not the last hurdle facing the TPP.

The most recent round of negotiations, held in Lahaina, Hawaii earlier this month, ended with negotiators unable to overcome familiar obstacles: dairy, automobiles, sugar, and various legal and regulatory provisions. In a joint statement released at the end of the Lahaina round, the TPP ministers claimed to be “more confident than ever that TPP is within reach” but did not set a date for further negotiations.

Three facts about the TPP standout from past U.S. trade agreements: its sheer size, the particular products included, and the scope of legal and regulatory provisions. The first point is perhaps the least important: the countries involved in the TPP include very large economies, but these economies already trade a great deal with each other. As is discussed below, it is unlikely that the TPP will radically reshape the aggregate flow of goods into and out of the United States.

However, what is ambiguous in the aggregate can be hugely important to particular industries or products. The TPP proposes to include a number of products, especially agricultural goods, that have traditionally been excluded from free trade agreements. Not surprisingly, these products have turned out to be key sticking points in the negotiations. Passage of many or even some of these agricultural items would be a significant step (forward or backward depends on your point of view) in the evolution of free trade agreements.

Finally, there are supra-national legal and regulatory provisions rarely seen in traditional trade agreements. TPP negotiators have set out to address areas that have little to do with reducing tariffs. Major issues include intellectual property rights, services, investor-state dispute settlement procedures, capital controls, and state-owned enterprises.[1. This list is drawn from Schott, Kotschwar, and Muir, “Understanding the Trans-Pacific Partnership,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2013.] In addition, China’s recent devaluation of the yuan has increased pressure for the agreement to address currency manipulation.

The Aggregate Picture: By the Numbers

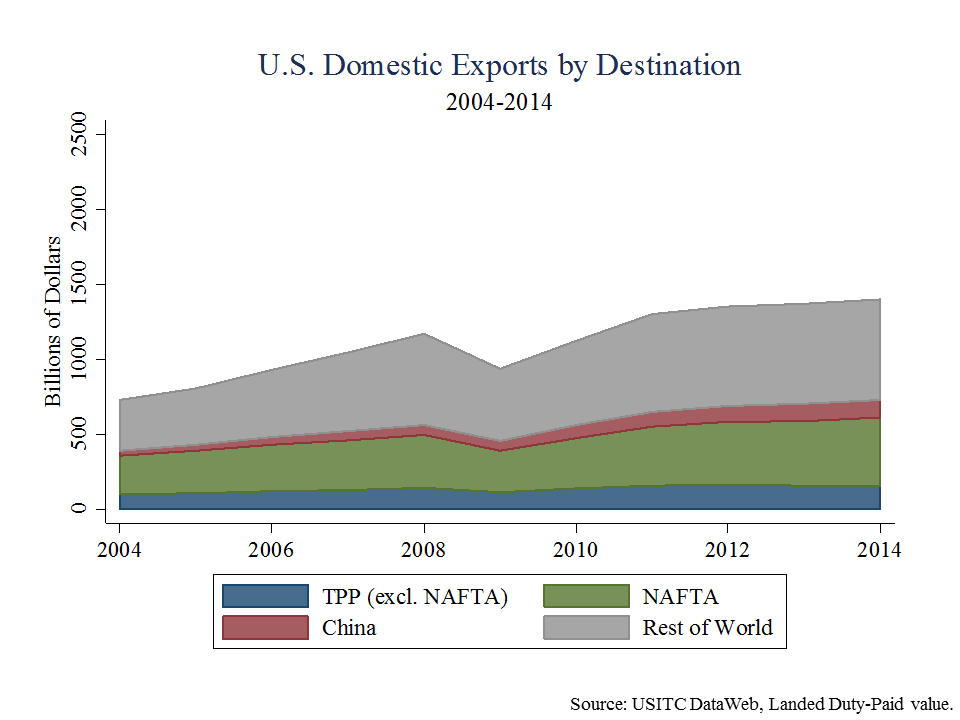

The number 40 comes up often in summaries of the TPP, as its member countries comprise roughly 40 percent of world Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 40 percent of U.S. exports and imports.[2. Trade figures come from the United States International Trade Commission’s DataWeb, comprising imports and domestic exports for all commodities. National macroeconomic estimates from the World Bank’s DataBank. Estimates of agricultural imports and exports are from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division. FAO estimates for Crops & Livestock Products and Live Animals have been aggregated.

From an American perspective, however, these figures may overstate the agreement’s potential importance. First, the United States makes up more than half of TPP members’ combined GDP. For Americans, the TPP would represent a trade deal with approximately 20 percent of the non-American global economy- not 40. Second, the U.S. already trades with most TPP members on fairly open terms. The United States signed and ratified the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico two decades ago, and has since reached bilateral agreements with Australia, Singapore, and Chile (the Washington Post has a nice illustration of these interweaving agreements). The figure below demonstrates that disaggregating the NAFTA countries puts the TPP in a rather different perspective.

Excluding Canada and Mexico, the TPP countries represent approximately 10 percent of 2014 U.S. imports and exports. In absolute terms, these trade flows have been fairly flat over the past decade, but declined as a share of total U.S. trade, owing to increased U.S. trade with other economies, particularly China, Canada, and Mexico. Much of the current wrangling over the TPP is not so much about the level of U.S. imports, but the source of those imports, as the Mexican and Canadian governments are concerned about losing privileged access to the massive U.S. market.

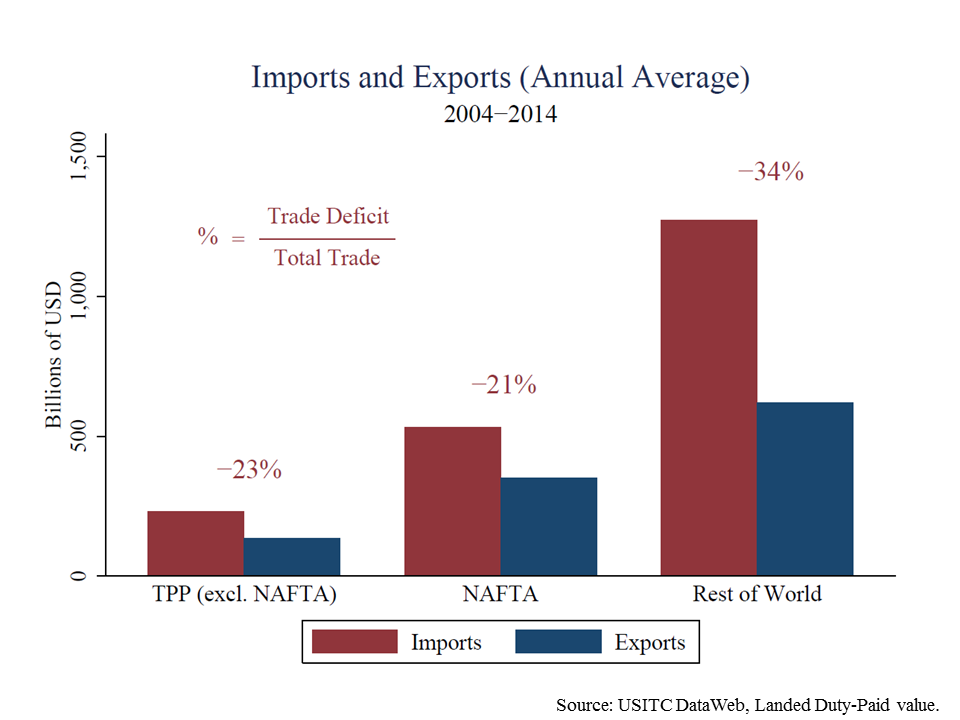

Regarding the trade balance, you will notice that the shaded areas in the top graph above (U.S. imports) are much larger than those in the bottom graph (U.S. exports). This reflects the U.S. trade deficit, as the United States has imported about $1.90 of goods for every $1.00 it exported over the past decade (the 2014 ratio was approximately 1.7). The relative trade balances may explain why the Obama administration finds the TPP appealing- at least compared to other potential agreements. The U.S. trade deficit (measured as a percentage of total trade) with the non-NAFTA TPP countries is significantly less extreme than with the rest of the world and comparable to the U.S. deficit with its NAFTA partners.

Although the TPP would further integrate a significant share of the global economy, it is not clear how large an impact would be made by a regional agreement lowering tariffs that are already quite low by global standards. The figure below shows the Weighted-Average Applied tariff rate for all TPP countries alongside the OECD and World averages, as estimated by the World Bank. There are numerous ways that calculating a single average tariff measure can be misleading but it provides a broad sense of the aggregate level of trade protection a country employs. These estimates suggest that, on the whole, the TPP members are fairly open economies.

The international trade literature suggests that moderate tariffs have minimal welfare effects and, therefore, eliminating such tariffs does not make a significant difference.[4. Feenstra, Robert. Advanced International Trade: Theory and Evidence. Princeton University Press, 2004. p.217] This may particularly be the case for the United States, as it has already entered FTAs with several of the more protected TPP economies (Chile, Australia, and Mexico) and therefore has fewer opportunities for significant tariff reductions. The figure below graphs the value of U.S. trade with its 111 largest trading partners against the value of trade predicted by a basic version of the gravity model of international trade.[3. The gravity model uses the size of two countries’ economies and the distance between them to predict the value of their trade. The model employed here uses only distance, economic size, and year fixed effects as explanatory variables- academic research controls for many additional factors. In particular, this model uses only US trade data and thus cannot control for country-specific fixed effects. This shortcoming is illustrated by the considerable underestimate of trade with Singapore and Malaysia, both of whom trade disproportionately to the size of their economies. In sum, the specific estimates should be taken with several grains of salt, but the findings of this rudimentary model are generally similar to more rigorous work (see for example: Rose, Andrew. “Do We Really Know that the WTO Increases Trade?” 2003.) and serves as a reasonable illustration.] The specific estimates are rough but the model broadly reflects the relationship between trade, economic size, and physical distance. This graph demonstrates that the TPP members (shown in red) are trading with the United States at least as much as one would expect given the fundamentals, and perhaps a little more. It is unlikely that a free trade agreement would raise the red dots in this figure dramatically above the trend. In other words, you can make a Pacific trade pact, but you can’t get rid of the Pacific Ocean.

None of this is to say that the agreement is unimportant. Rather, it highlights the fact that the main points at issue in the TPP are more about particular products and supra-national regulatory details than across-the-board tariff reductions. In fact, about the only thing that both TPP supporters and detractors can agree on is that the TPP is not just about tariff reductions. The proposed agreement is believed to address intellectual property issues, state-owned enterprises, services, and other provisions not related to the trade in physical goods. Supporters like to say that these provisions make for an “ambitious, next-generation” or “high-quality” agreement. Detractors consider them to be nothing more than a “Corporate/Investor Rights agreement” dressed up in Free Trade clothing, or a “Trojan horse in a global race to the bottom.” Whatever one thinks of the debate, both sides are correct in pointing out that tariff reductions, in the aggregate, are not the most important component of the talks.

Agricultural Issues

Agriculture is one of the most difficult issues in FTA negotiations. It was at the center of the WTO’s failed Doha Round and is seen as “the major piece of unfinished business from previous trade rounds.” A primary difficulty for agriculture is that developing countries tend to have comparative advantages in agricultural products and the issue thus pits rich and poor countries against each other in the negotiations.

The dynamic is different for the TPP. With the significant exception of Japan, most TPP nations are either net exporters of agricultural goods or are fairly even in the balance between imports and exports. Compared to most countries (especially most developed countries) the TPP nations are more inclined to expand agricultural trade because a) they would benefit from increased exports and, b) their farming sectors are relatively more resilient to import competition. Excluding Japan, the combined TPP nations export $1.44 of agricultural goods for every dollar they import.

Also unlike Doha, there is not a clear rich-poor split in the agricultural trade orientation of TPP nations. There are rich net exporters (the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand) and poor net exporters (Vietnam, Peru); rich net importers (Japan, Singapore)and poor net importers (Mexico). For these reasons, one might expect agriculture to be less divisive for the TPP negotiations than other plurilateral trade agreements. That it has not been any less divisive suggests that the agriculture negotiations are not so much focused on across-the-board tariff reductions but the lowering of protections for particular products in particular countries.

The Japanese exception to the trends shown above is worth highlighting. Outside of China, Japan was the world’s largest net importer of agricultural products in 2012, when it imported approximately $20 of agricultural goods for every one dollar it exported. On this metric, Japan ranks globally alongside the likes of Mauritania and North Korea. Japan’s highly protected agricultural market is thus one of the major ‘prizes’ motivating countries’ participation in the TPP. However, it is unclear just how much liberalizing Japan is willing to do. Japan currently charges a 778 percent tariff on rice above a minimum-access quota, a 252 percent tariff on wheat, 360 percent on butter, and 328 percent on sugar.[5. Elms, Deborah. “Agriculture and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Negotiations.” Trade Liberalisation and International Co-operation: a Legal Analysis of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, ed. Tania Voon. 2013] Each of these falls under the “five sacred” products widely considered off-limits in Japanese politics and there has yet to be any clear indication of which products, if any, will see significant tariff reductions. One imagines that access to the Japanese market is the primary motivation for Vietnam’s interest in the TPP, and also for certain key interest groups in other countries. If Japan does not agree to significantly lower its agricultural tariffs, the enthusiasm of many pro-TPP actors could be severely diminished.

The Particulars: What do Japanese brake pads, Australian sugar cane, and New Zealand cheese have in common?

The aggregate trade flow effects may be ambiguous, but the potential impacts of the TPP on particular products or national industries are quite clear. The opinions of Japanese rice farmers, Canadian dairy producers, and U.S. autoworkers are far from ambiguous.

Negotiations over particular sectors can be difficult even if- perhaps especially if- the United States has already concluded free trade agreements with some of its major trade partners in those sectors. Auto-parts, sugar, and dairy products have proven to be significant stumbling blocks to the negotiations, with U.S. market access as the key sticking point. In each case, however, it is not only U.S. industry groups protesting, but also the United States’ NAFTA partners: Canada and Mexico.

In the automobile sector, U.S. negotiators agreed to a Japanese request regarding the trade of non-TPP origin automobiles and parts (a significant share of the components in Japanese cars are produced elsewhere in Asia, particularly China and Thailand). This led Canadian and Mexican auto-parts makers to send a joint letter to their respective trade ministers to reject the provision, in hopes that they not lose out on privileged access to the U.S. market.

Australian negotiators have been focused on gaining greater access to the U.S. sugar market. The situation is complicated by the fact that the U.S. and Mexican governments recently concluded an agreement governing the amount of Mexican sugar allowed into the United States (Capital Trade’s Seth Kaplan served as an expert for the Mexican industry in the case before the U.S. International Trade Commission). Increased Australian access could take up market share from the United States, Mexico, or both.

Triangulating the state of dairy negotiations is particularly interesting. The U.S. industry has nothing to gain from allowing greater market access to major producer New Zealand. However, the U.S. dairy lobby officially supports the TPP , in large part because it hopes to gain greater access to the Canadian market in the process. Canada has numerous dairy protections that survived both the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement and subsequent NAFTA agreement. Canadian “intransigence” on this issue inspired a letter from 21 members of Congress to the Canadian government. One assumes that Congressional support from say, Wisconsin, will hinge on the Canadian position.

That agricultural products have become major obstacles in the negotiations comes as little surprise. Indeed, the Peterson Institute’s policy analysis Understanding the Trans-Pacific Partnership, published in January 2013, lists dairy and sugar as item numbers 1 and 2 in its chapter: “Sticking Points to the Negotiations.” Whether compromise on these issues is- or ever was- possible remains to be seen.

Legal and Supra-National Regulatory Provisions: Toward a Brave New World

As argued above, the expected legal and regulatory provisions of the TPP are perhaps the most significant aspect of the agreement. The most contentious of these provisions, according to Schott, Kotschwar, and Muir, are intellectual property rights (including the difficult issue of pharmaceutical copyrights), services, investor-state dispute settlement procedures, capital controls, and state-owned enterprises.

These issues are too complex to analyze in any detail here, but consider one key characteristic of the TPP that makes negotiations so difficult: the economic diversity of its member countries. The figure below charts the 2014 per capita GDP of the TPP countries.[6. These amounts are in nominal terms because trade takes place in nominal dollars- not Purchasing Power Parity-adjusted dollars.] Not only is there a wide range from top-to-bottom, there is also a major gap in the middle between Chile and Japan. In regards to their level of economic development, TPP countries are both diverse across the board and split down the middle. One can expect heterogeneous policy preferences from a group that includes Vietnam, Brunei, and Canada.

Diversity can be a motivator for trade if there are complementary comparative advantages (for example, India exports labor-intensive goods to Germany and Germany exports capital-intensive goods to India). However, this is not at all the case for regulatory provisions. For example, why would Vietnam agree to restrict the actions of its state-owned enterprises? Why would Peru want to protect U.S. pharmaceutical copyrights? The only plausible answer is that these provisions are a part of tit-for-tat exchanges inherent to these types of negotiations. Such exchanges can make sense, on paper, but this makes for a complex coordination game between the negotiators and a single domino falling can have effects in seemingly unrelated areas. For example, if Japan balks on granting access to its rice market, is Vietnam really motivated to regulate its state-owned enterprises? If not, is the U.S. going to make concessions to Vietnam on textiles? What will Peru think of a deal without U.S. textiles concessions? And so forth.

In view of the above, it should come as no surprise that the administration is having trouble closing the deal on the TPP. Fresh off its victory in passing fast track, the administration now faces a different kind of track, with hurdles both familiar (sugar and dairy) and novel (regulatory tradeoffs among multiple countries). The TPP is a new age trade agreement that goes well beyond import duty reductions. It turns out that concluding such agreements on a plurilateral basis is extremely difficult–and maybe even impossible.